Introduction

Figure 1 Exterior of church (left) Sheffield City Centre (right)

On April 2nd – 4th, the AF team engaged with a cohort of enthusiastic undergraduate and graduate architecture students from Sheffield Hallam University to investigate the potential for adapting St. Vincent’s church and its large multi-tiered site that houses a collection of derelict buildings. The three day workshop involved a series of exercises designed to encourage students to think about adaptability, the site and the use of film as a medium to communicate their architectural interventions. The aim was to broaden their approach to design by thinking about their intervention(s) as a serious of small, incremental changes over time rather than one large transformational step at a single point in time, integrating ideas around time and change through a time-based medium (film), using new software.

Day one

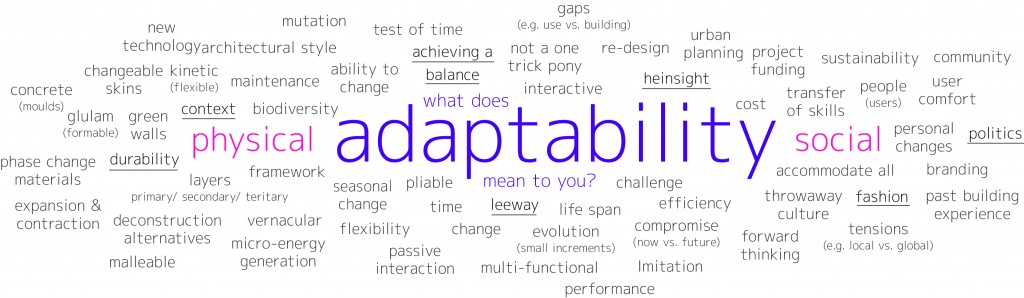

What does adaptability mean to you?

Figure 2 Students present ideas about adaptability

After brief introductions, the students broke into three groups and spent the morning discussing adaptability. The first exercise asked the students, ‘what does adaptability mean to you?’ After brainstorming their thoughts on post-its each group stuck their ideas on the wall and presented some of their core thoughts for discussion. The students immediately picked up on some of the core issues surrounding adaptability, including looking both to the past as well as the future, allowing for an appropriate level of leeway and the interplay of context and the building. The dialogue allowed the students to make connections between contingencies which exist outside the conventional understanding of what constitutes adaptability, unravelling synergies and tensions between several issues. Figure 3 below captures the topics raised by the students with the underlined text highlighting some of the ones elaborated on in discussion.

Figure 3 Graphic capturing thoughts about adaptability

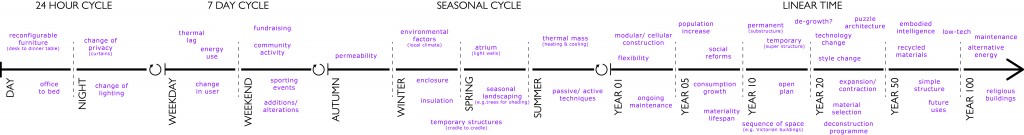

Types of change

The second exercise asked the students to think about the types of change that a building may have to endure over its life and plausible solutions to accommodate those scenarios over time. In a similar fashion as the first exercise students discussed this in groups before presenting their thoughts to the collective. They were asked to plot the scenarios and solutions on a timeline which featured cyclical periods of time (24 hour, 7 day and seasonal) as well as a linear timeline (Figure 3 and 4). The exercise provided an opportunity for the students to think about how a building might need to change to accommodate different needs or conditions from day to night, weekday to weekend, spring to winter and over years of use. An example of a solution that was talked about was the use of seasonal landscaping (e.g. shading from trees) to help mitigate climatic changes throughout the year rather than the use of mechanical systems. On the long-end of the timeline certain materials, building systems and use types were debated as lending themselves better to long-life durability and flexibility (and social acceptance). An array of ‘side’ topics arose from the exchange including the fact that they had never really had to think about the long-term reality of buildings, particularly how to design for it. One aspect that became clear is that all design interventions are temporal and whether we have designed for it or not, buildings change, so how can we ease the accommodation of that change while allowing for the integrity of our design to remain (since facility managers and/ or users probably won’t)?

Figure 4 Graphic illustrating captured changes/ solutions over time

Figure 5 Students present change scenarios

Site Investigation

After lunch, the students went to investigate and document the site. In a slight contrast to simply photographing the site, students had to think about capturing sequence(s) of images rather than the perfect image to superimpose on to – the possibility of time lapse, dynamic photo montages and sequence photography are all methods to incorporate time into photography. The integration of time reinforces the student to think about how one experiences or moves through the building, the site or the surrounding neighbourhood as opposed to a static object in Cartesian space. It also strengthens understanding the building in its context as it begins to construct a narrative. These of course are not new to architectural thinking, but an evolution in its explicit consideration as part of the representation/ communication process (for more on this thinking read Latour and Yaneva 2008, Give Me A Gun and I’ll make all buildings move).

The site, whilst only being a 10 minute walk away, felt disconnected from the city centre, separated by the B6329 – underlined by the fact that many of the students had never been past the church before. The church’s site sits atop a hill and is heavily sloped and tiered into two main levels – the lower level consisting of a group of ancillary buildings. At first glance, the exterior of the church appears like any other of its period that is still in operation, supported by the full parking lot (on both tiers). But upon closer inspection the car park functions as a commuter parking lot, physical signs of a lack of care are evident and made abundantly obvious once stepping through the main door (Figure 5) where the interior of the church has been stripped of all its religious valuables and moved to the congregations new home 11 years ago. The interior now is filled with an interesting sea of eclectic items, ranging from a large sofa chair to a hoover from the early 90s. One can easily see traces of what was a beautifully ornate space with some of its décor in remarkably good condition while other pieces (including the confessional booths) in great disarray.

Figure 6 Interior of St. Vincent’s church

The students spent an hour documenting the site before retreating to the architectural office of Race Cottam, located on the adjacent corner, to hear from Mathew Hayman from the City Planning Department. Matt presented a historic overview of the area (or quite simply its deterioration) and how the council hoped to see the site (re)developed in the future. The presentation made clear the ambition for the church to once again become a focal point of the community, but at the same time illustrated the many issues which have hindered its reuse (e.g. perception of safety, neighbouring buildings, and low footfall in the area).

Opportunities and constraints of the site

Upon returning to the studio, students split back into their groups to reflect on the site conditions (constraints and opportunities), which were captured in a third discussion. Many of the issues came out on both sides of the coin depending on how they were interpreted, some of the key topics discussed were the lack of amenities in the area, the building’s historic value, its massive scale, site accessibility, ownership and building regulations (the topics are captured in Figure 7 below). Some of the key questions amongst the groups that began to take prevalence included:

- How can better use be made of what they have now?

- What are the quick wins that can be done without large investment from any one organisation?

- What kind of temporary activities (quick and dirty) could draw a range of groups together to generate excitement and appreciation for the site in preparation for a larger investment in the future?

- Who would want to take on a longer term investment in the site? How could this be shared amongst different organisations?

- In building momentum, how do you engage with the growing, energetic, yet transient community of students in the area, providing them with a reason to interact with the site?

- Can you connect to/ build off of the soon to be complete Edward Street Park (what value / activity will that add to the area)?

- Can you tie into one or both of the universities or the success of the Creative Arts Development Space (given the neighbouring student accommodations)? (i.e. how do you link to large communities not necessarily associated with the area)

- Can you connect to the commuters who use the parking lot? (e.g. day care/ after school programme?) Or with the owner/ church community?

- Can you improve on the site’s connectivity to the centre? The surrounding uses/ amenities?

- How do you use and/ or improve on the area’s topographic barriers?

Figure 7 Opportunities and constraints around the site

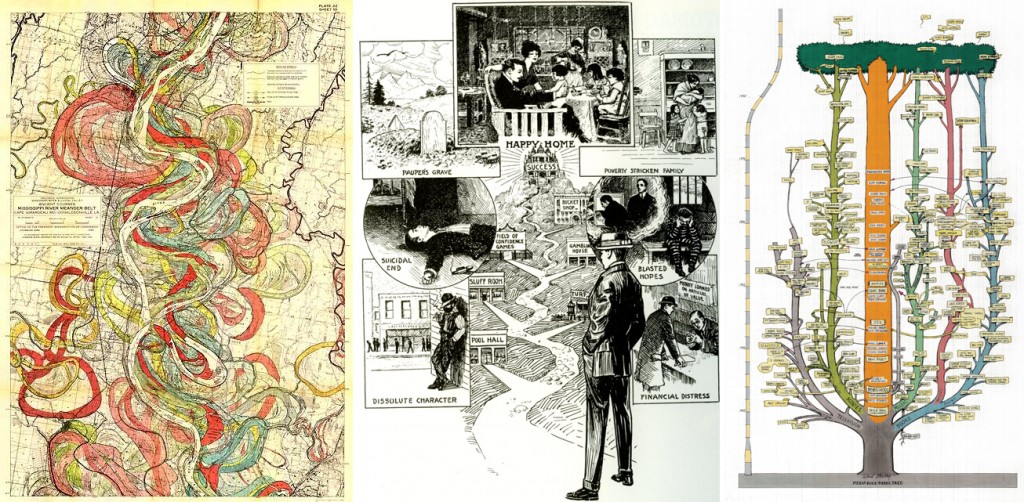

Mapping and Storyboarding

The day concluded with a presentation on visualising (mapping) information and storyboarding in an effort to get the students to begin to think about alternative ways of visualising the site outside of conventional architectural methods – i.e. how might they use film as a medium to convey the dynamic aspects of the issues at hand by conveying a narrative of architectural intervention (Figure 8). The students were introduced to a three step process as a way of developing their ideas – sketching out a storyboard, animating the storyboard (animatic) and finally developing the animatic into a film. As a first step the storyboards can explore several aspects of the finished film including the narrative, scene, filming technique, sound, action, etc. The animatics are meant then to further ‘test’ those ideas by quickly ‘mocking up’ the movie using the imagery from the storyboard with rough timings, effects, transitions, audio, etc. To help them visualize the intended output, students were then shown some examples of animatics and films from the AF website illustrating examples of how to bring to life the concepts considered in the storyboards.

Figure 8 Mississippi River bed changes over time (left) Edward Tufte’s Path of life (center) Ward Shelley’s Media role models (right)

Day two

Day two started with the students developing their ideas via informal tutorials and sketching them out prior to returning to the site to gather additional footage and/ or images for their films. The afternoon was spent with an introductory tutorial on Adobe After Effects (a composition and motion graphic software) which served as the primary software for developing their films (in addition to some use of Adobe Premiere and Quicktime Pro). While potentially being utterly complicated, the familiar interface of Adobe allows the students to quite quickly understand the basics and see the intriguing possibilities of the software. In many ways it is very much like developing layered images in Photoshop, but with the associated use of a timeline to allow the layers to change over time. The tutorial presents a foundation for how they can use the software to create their films (or comedic animations of ‘dead’ pigeons found in the building the day earlier).

Figure 9 Adobe After Effects Interface

Day three

On Wednesday the students spent the day developing their storyboards and film ideas. In the afternoon, we were joined by Ivan Rabodzeenko from SKINN, a not-for-profit development agency working in the area (Shalesmoor, Kelham Island & Neepsend, i.e. SKIN Network). Ivan gave the students a brief introduction to SKINN and the interesting work they’ve been doing in the area (including the CADS development). The students then presented their work from the three days, which while still evolving, allowed the groups to communicate and share their thoughtful and interesting responses to the conditions at hand. Playful yet viable interventions of scattered billboards, a slice through the building and site and strategically inserted studio pods presented some entertaining food for thought. The next step involves each group taking their ideas forward and submitting a finished film to our student design competition at the beginning of June. The competition provides the students with an incentive to have their work aired to a wider audience. In addition, the students will also have the opportunity to exhibit their films at CADS this summer.

Figure 10 Student storyboard example

Concluding Thoughts

The workshop sought to encourage students to think beyond an immediate design solution and to understand the possibility for making tactical design interventions over time. Creating a film gives the students a new skill that they can use in future projects. Film serves as a familiar way to communicate to (and engage with) a broader audience outside of the architectural and construction community, and can help provide an increased capacity to imagine how the site could be transformed now and in the future. The workshop is our third of its kind and is contributing towards a revised perspective on architectural education. The workshops themselves have become a great platform for engaging the community, council and the students in a discussion forum, where the students bring fresh ideas and knowledge from a demographic which is generally underrepresented in these types of conversations. The council and community bring real design considerations and a valuable voice that differs from their tutors. The workshops have received positive feedback from the students as an opportunity to a) develop a new skill, b) take a refreshing break away from their yearlong projects and c) sharpen their design thinking and illustration skills; whereas, on the other hand, the community organisations and council see it as an important way to communicate design ideas and to excite the broader community about the possibilities to change an area. There is a plan in the works to run a longer and cross-disciplinary workshop in Sheffield this autumn.

Comments

Leave a comment: